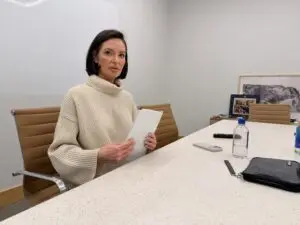

Julie Bushell of Global Sustainability Developers LLC. (Aaron Sanderford/Nebraska Examiner)

—

Aaron Sanderford

Nebraska Examiner

LINCOLN — Gov. Jim Pillen, while pressing the Nebraska Department of Economic Development in 2024 to tighten its belt, steered the state agency to award a $2.5 million no-bid emergency contract to a bioeconomy consultant and lobbyist he knew and had traveled with as part of state delegations.

State Auditor Mike Foley alleges the Economic Development Department, in carrying out that Pillen-picked contract, broke state law by not specifying in writing what emergency justified skipping the required step of bidding out contracts worth more than $50,000, a step meant to save taxpayers money.

In a Jan. 6 audit letter Foley shared with the Governor’s Office, which was obtained by the Examiner and authenticated by the auditor, Foley dinged the department for leaving blank a required section for explaining the emergency on the state’s “Procurement Exception/Deviation” form.

That’s where department personnel must explain the circumstances justifying seeking no bids. Foley criticized the agency for leaving the second page of the May 2024 form blank, writing that it “contained questions regarding the reasons for designating the contract as an emergency.”

Foley’s letter alleges that omitting this information meant the contract did not comply with “the legal requirement to specify the nature of the supposed exigency” under the Nebraska State Procurement Act in Nebraska Revised Statutes 73-815.

That section of state law requires the agency to provide the “justification of the emergency” and requires the state to “retain a copy of the justification with the contract in the state agency files.” Violating that law carries no criminal or civil penalty.

According to Foley, the designation of the contract “as an ‘emergency’ is unsupportable.” The absence of a bidding process, Foley alleged in the letter, resulted in a $2.5 million contract for Global Sustainability Developers LLC, “a company handpicked rather than selected through the ‘time-honored’ and legally required open, competitive process.”

“I think it’s critically important, because competitive bidding is a bedrock, foundational tenet of government operation,” Foley told the Examiner of his findings. “When you sidestep a foundational tenet, it’s just waving a huge red flag for any public auditor. It smacks of favoritism.”

Contracting with GSD

Nebraska awarded the $208,333-a-month, remote work contract in May 2024 to GSD, a Lincoln firm that at the time had a single employee — owner Julie Bushell, a lobbyist with agricultural and telecommunications connections who also leads Ethos Connected, an agribusiness firm using sensors to wirelessly connect farm and ranch infrastructure, including water.

The state contract with GSD called for Bushell’s firm to drum up more bioeconomy business in Nebraska, including by accessing more federal funds for such developments.

Nebraska’s contract with GSD was the Department of Economic Development’s largest emergency no-bid contract since the COVID-19 pandemic, the Examiner found and state officials confirmed.

It was far larger than a typical emergency no-bid contract, with some notable exceptions during the pandemic, based on a recent legislative performance audit of state handling of emergency contracts. The median emergency no-bid contract in Nebraska between 2014 and 2024 was about $350,000, it found.

The auditor’s report, as well as Examiner reporting, make plain that Pillen’s office recommended the contractor on behalf of the governor. Pillen’s chief of staff, Dave Lopez, was among staffers involved in the process, based on records and messages obtained by the Examiner. Chiefs of staff often communicate with state agency leaders.

DED leaders did not know firm

State correspondence indicates that top Economic Development Department leaders did not know the firm they were contracting with when the contract was awarded, based on the Auditor’s Office letter and backed by months of interviews, public records and reporting by the Examiner that started before learning of the auditor’s probe.

But Pillen knew Bushell’s work. She had joined Pillen on state trips to South Korea and Japan, records indicate. She also joined some state delegations when Pillen visited Washington, D.C. Both attended the 2024 Republican National Convention in Milwaukee. A photo obtained by the Examiner shows Pillen and Bushell together at the 2024 Aksarben Ball, held by a charitable foundation of business leaders.

To the Examiner, the Governor’s Office denied playing favorites.

Foley said Pillen told him when they talked during the audit that he himself had recommended Bushell.

The auditor said the governor, in the same conversation, described the decision as a joint one between Pillen and the DED director at the time, K.C. Belitz.

Emails between then-DED leaders, including Belitz, show the Governor’s Office’s involvement in the contracting process. Belitz did not return calls or messages seeking comment, but his correspondence says the language of the contract was “vetted thru Julie [Bushell] and the Governor.”

Governors hire and fire the leaders of many state agency departments, including the Department of Economic Development.

Belitz resigned in June 2025. Pillen replaced him with his general counsel for the Governor’s Office, Maureen Larsen, who also previously served as deputy director of Pillen’s Policy Research Office.

“I’ve been in the [Capitol] building 25 years, 11 years as an auditor, and I can’t recall anything that had the direct involvement of the governor,” Foley said.

Contract facts

Of about 4,200 contracts entered by the state in each of the past two calendar years, 22 in each year were emergency contracts for which the state sought no competitive bid, according to the Nebraska Department of Administrative Services, the state’s clearinghouse for such contracts.

Under the Nebraska Procurement Act, DAS is “the sole and final authority on contracts for personal property by a state agency,” including for no-bid emergency contracts.

Including the GSD contract, only five of the state’s 44 emergency no-bid contracts over the past two years left the justification blank, DAS says. Three of the five were DED contracts, officials said. Two were on behalf of DAS itself.

From mid-2020 through 2025, the Department of Economic Development signed a total of four emergency no-bid contracts, officials said. Two paid six figures. One was for five. GSD’s was for $2.5 million.

Pillen’s team blamed a former DED attorney for not adding the legal justification to the GSD contract and the others. But Pillen-led DAS signed off on the GSD contract without the justification, copies of the contract indicate.

Lee Will, director of the Department of Administrative Services, said last week that the state contracting office, after Foley’s audit, had revised its Deviation Form to make clearer that the justification section must be filled out and added a step to its processes to make sure the required box is completed.

Foley said he would like his office to join the process. State Sen. Bob Andersen of Sarpy County introduced Legislative Bill 997 Tuesday on Foley’s behalf that would require an additional copy of state no-bid contracts, including emergency no-bid contracts, to be filed with the State Auditor’s Office, in addition to the agency and DAS.

The Governor’s Office, over several days last week, told the Examiner Pillen recommended contracting with Bushell because of her business connections, leads on potential development projects and experience in maximizing how much federal money Nebraska could secure at the end of the Biden administration.

Pillen spokeswoman Laura Strimple said the Governor’s Office has supported two emergency no-bid contracts “when the Legislature passed requirements to engage vendors in a certain timeframe, and the cumbersome procurement process would not have met the deadline.”

Both have helped taxpayers, she argued, and “delivered overwhelming value to Nebraska.” One was the DED contract with GSD. Another was a $10 million, four-year state contract with Utah-based Epiphany Associates and the Department of Administrative Services to help DAS use technology to find potential “systemic cost savings across state government.”

“The bioeconomy contract delivered hundreds of millions to Nebraska, and the DAS cost-reduction effort continues to produce lasting reforms in cost-cutting efforts for the state,” Strimple said.

The Epiphany contract drew legislative scrutiny during the 2024 session, including questions from state senators about whether leadership of the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services should have disclosed previous ties to the company.

Governor’s Office: Bushell helped state get funds

Team Pillen says Bushell’s business, GSD, helped Nebraska secure $550 million in federal funds — about $200 million of which have yet to arrive. Among the funds mentioned, the administration says Bushell helped the state secure $33 million in U.S. Department of Agriculture funds for Affordable Clean Energy Loans to Sandhills Energy and Bluestem Energy Solutions and $10.3 million in Rural Energy for America grants and loans.

The $200 million USDA New Era grant to Nebraska Electric G&T is the part that had not yet been disbursed, Foley’s letter says.

Pillen’s staff also credits Bushell with a pledged investment of at least $5.5 billion to build a cornstalk converting biofuels plant in Phelps County, in the Holdrege area.

Former Phelps County Development Corporation director Ron Tillery called Bushell’s help vital.

Tillery said Pillen suggested during a visit to Phelps County in July 2024 that local economic development officials should meet with Bushell if they were serious about pursuing a sustainable aviation fuel plant, which locals wanted as a means to carve out a market niche in a world of ethanol and biodiesel plants.

Kenny Zoeller, who leads the Governor’s Policy Research Office and spoke for Pillen’s team, said Bushell came recommended by Nebraska business leaders and “Aksarben,” which is often shorthand in political circles for a group of statewide business leaders sometimes loosely tied to the Omaha-based Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben organization.

Three people with ties to the group questioned whether its leaders would recommend a contractor for a state bioeconomy consultant, and more than one said Pillen had introduced members of the group to Bushell. Bushell joined the group’s board in mid-2024, archives of the foundation’s website show.

Bushell, in a sit-down interview last week, echoed the Governor’s Office in saying the economic benefit to Nebraskans of her work helped the state obtain more federal money than it might have otherwise. She said her contacts in the bioeconomy space helped land planned projects like Phelps County’s DG Fuels plant.

The Pillen administration, through Zoeller and Will, argued that Bushell’s work helped Nebraska secure nearly $290 million more in federal funds than a per-capita projection of what the state should expect to receive.

“I think the deliverables of this contract speak for themselves,” Bushell said. “I am incredibly proud that the world knows that Nebraska is the leader in bioeconomy, and in an economic position that the state’s in now. I think it’s really important that we continue to grow and invest in these projects.”

Foley argued that the administration’s per-capita number ignores that most such federal projects run through more complex formulas that consider much more than population. He noted in his audit letter that “other states received comparable amounts of the same grant and loan monies, presumably without any involvement by GSD.”

Questions about DG Fuels

Foley’s audit letter also questions whether Nebraska and Phelps County economic development officials are banking on a $5.5 billion DG Fuels project that might not be built.

The audit team dug into 11 announced DG Fuels projects in 10 states since 2001, seven of which pledged investments of more than $1 billion. The Foley letter indicates that none of the DG Fuels projects his team reviewed has yet been built to completion, although the audit shows several of the projects have made progress.

Among them: a sustainable aviation fuel plant planned for the former Loring Air Force Base in Maine, where the audit said ground was expected to be broken in 2026, and a 2024 announced project in St. James Parish, Louisiana, which expects to start producing fuel in 2028.

Washington, D.C.-based DG Fuels, a biofuels and sustainable aviation fuel developer, did not return multiple Examiner attempts over several days to reach the company by phone and email.

Michael Darcy, the owner of DG Fuels, originally agreed to sit down with Foley’s team, the auditor said. But Foley said Darcy and his company cut off communication before the two met, after Foley communicated that he planned to question the progress of projects in other states.

Bushell said Nebraska needs to be careful not to create an environment that costs the DG Fuels project. She and Tillery say the project is making more progress through the state and local permitting process. Bushell said DG Fuels told her the Nebraska project is among its top priorities.

Foley’s audit letter also highlights that Bushell sought in October 2024 to amend the conflict-of-interest provision of her state contract so she could negotiate with DG Fuels about possible future work after the state contract ended. She did not respond to the Examiner’s follow-up questions about that push via text or email.

DED, with the Governor’s Office’s knowledge, approved the contract change. Will, in a statement to the Examiner, said the department “felt the revised terms would not lead to a conflict of interest.”

“In short, there was no risk for a conflict of interest, because there was no funding to create a conflict while under state contract,” Will said.

Foley said such conflict of interest language is meant to protect taxpayers and that he had unanswered questions about Bushell’s push to negotiate with a private company she had been working with on the state’s behalf.

“The Phelps County project is one of the trophy projects that supposedly came from this [contract],” Foley said. “There were a number of federal grant awards that they say came because of GSD. … When our auditors looked into it, other states were able to get similar amounts.”

Too little time?

Foley, in his letter, wrote that DED had enough time “to search for a qualified service provider in compliance with statutory competitive bidding requirements” for the $2.5 million bioeconomy contract that went to GSD.

But Zoeller and Will pushed back, arguing that Legislative Bill 1412, the mid-biennium budget bill, left the state too little time to act when it took effect in early April 2024.

The bioeconomy provision in the budget bill required DED to coordinate work aimed at bioeconomy development, seek federal grants, and it gave the agency 15 months to report back on its progress. The law did not require immediate spending or entering into a contract.

The Governor’s Office pointed to the law’s requirement for a status report on the new bioeconomy initiative to the Legislature by June 30, 2025. According to Zoeller and Will, issuing and evaluating requests for proposals takes up to 60 days, followed by an RFP protest period of up to 50 days, which meant completion without the emergency approach could have taken up to 110 days.

But Foley said because the Governor’s Office sought that section of LB 1412, the Department of Economic Development had early warning and could have started its processes sooner to be ready to go out for bids and could have sought requests for information to gauge interest sooner from potential bidders.

Contract obligations questioned

Foley’s questions about the contract stretched into how little it required of GSD in terms of reporting how the firm spent state money. It did not require itemized receipts of expenses or time sheets. It required only the submission of monthly invoices summarizing the work done and dollar amounts, he said.

Those invoices largely say Bushell’s firm helped introduce state and local leaders to bioeconomy developers, scheduled and attended meetings, lobbied federal agencies and contacts, reviewed and discussed grant applications and communicated with project planners.

Will said that, while Foley was right that many state contracts are stricter with reporting requirements for the spending of state funds, some state contracts with consultants, including many in economic development, leave more flexibility to let consultants spend the funds more nimbly.

The State of Nebraska pushed to end Bushell’s contract two months early, at the end of February 2025. Zoeller told the Examiner the change in presidential administrations meant that Nebraska and Pillen had a more direct relationship with the Trump administration and no longer needed GSD’s connections. Foley said he started requesting information about the state contract in mid-January 2025.

In the end, the state paid Bushell’s firm $2.08 million. What Nebraska got for that money, Foley said, remains unclear. Pillen’s team says the state got a more than reasonable return on its investment.